This is Part 2 in our 2 part series – a reprint of a chapter in the recently-released “Sunshine/ Noir II – Writing from San Diego and Tijuana“, an anthology of local writings compiled by Kelly Mayhew and Jim Miller and published by City Works Press. Here is Part 1. For a copy of Sunshine/Noir II go here

The Story of How a Small Working-Class Coastal Community Within San Diego Spoiled the Establishment’s Plans and in the Process Created a Revolution in Urban Planning

The Story of How a Small Working-Class Coastal Community Within San Diego Spoiled the Establishment’s Plans and in the Process Created a Revolution in Urban Planning

Part 2

By Frank Gormlie

While it participated deeply in the negotiations during the remainder of 1974 and into the next year, the Community Planning Group had enough depth to juggle its activism and successfully respond to new construction projects—mainly large, bulky apartments—still coming down the development pipeline. Over this period CPG was able to block the construction of eight five-story high-rise apartments, most of them aimed for the fragile edges of Sunset Cliffs.

With the limited consensus reached on certain issues by the Committee of 12/16, in Spring of 1975 the city published a brand new Precise Plan—complete with a colorful cover. This was the formalization of the earlier Draft Revision and carried more weight, and again, it confirmed the city’s rejection of the worst of the original plan; no mini-Miami Beach, no marina, no high-rise along the coast. Yet, still it had major faults, and activists were disappointed that there hadn’t been more progress between the Draft Revision published in January 1974 and the latest version, put out over a year later.

For activists, the chief problem with the new plan was the lack of an outline for the democratic selection of representatives to a committee that would implement the Plan. The revision also allowed a 33% increase in population density over a period of time—no one wanted to see that kind of massive growth. It called for a main north–south feeder street to be made one-way and directly connect with an extension of the I-8 freeway, OB’s main link with the outside. From its beginnings, CPG opposed one-way streets as they become barriers to intra-community transit, cohesion, and “neighborliness.” And no one wanted to see the large under-developed sports area, called Robb Field, sliced up. Finally, it lacked any plans for the development of low and moderate income housing.

Immediately, CPG launched yet another petition drive—this one to add its own amendments to the city’s new plan, amendments to nullify some of the worst of that version, and one that called for a community-wide election process for a planning committee. After three to four months, volunteers had collected a hugely substantial 3,500 signatures from locals, in a community with only about 13,000 residents. Meanwhile, the Plan had gone before the Planning Commission in April 1975 and before a City Council sub-committee in mid-June.

Immediately, CPG launched yet another petition drive—this one to add its own amendments to the city’s new plan, amendments to nullify some of the worst of that version, and one that called for a community-wide election process for a planning committee. After three to four months, volunteers had collected a hugely substantial 3,500 signatures from locals, in a community with only about 13,000 residents. Meanwhile, the Plan had gone before the Planning Commission in April 1975 and before a City Council sub-committee in mid-June.

July 3, 1975 was the fateful day the City Council heard the OB Plan. It was standing room only in the Council Chambers, which brimmed with residents, property owners and merchants from OB. It was the scene that mirrored that “sea of blue” showdown that came four decades later. In 1975, after all the public testimony and speeches, after more discussion among the politicos, the San Diego City Council—with Republican Mayor Pete Wilson at the ceremonial helm—took a vote and passed the OB Precise Plan—and with a number of CPG’s amendments. The most important—the provision for a community election of a planning committee—was included.

The City Planning Department was ordered to implement a Planned District for Ocean Beach, from the motion itself:

[T]he new committee formed for the purposes of implementing the Plan, should be elected by the citizens of Ocean Beach in a democratic fashion, using a process monitored by a neutral party to be appointed by the Mayor and Council.

This was truly an historic vote by the San Diego City Council—for never before in the history of the city had a neighborhood been authorized to hold its own special election for its local planning committee. This was to be a first for any community in the city.

OB residents and activists returned home full of hope and pride that they had won a significant victory, a victory torn from the mouths of Pen, Inc. The sheer weight of their numbers, their signatures, their petitions, their persistence over four years had upended the establishment plan for the community. The people had revolted and had forced the implementation of a never-before-allowed element of community planning—an election of local planners; it was indeed a democratic revolution in the arena of urban planning, a furtherance of democratic rights for a working-class community. Any “citizen” could vote in this OB election—even renters, and of course, OB then, as now, had lots of them.

OB residents and activists returned home full of hope and pride that they had won a significant victory, a victory torn from the mouths of Pen, Inc. The sheer weight of their numbers, their signatures, their petitions, their persistence over four years had upended the establishment plan for the community. The people had revolted and had forced the implementation of a never-before-allowed element of community planning—an election of local planners; it was indeed a democratic revolution in the arena of urban planning, a furtherance of democratic rights for a working-class community. Any “citizen” could vote in this OB election—even renters, and of course, OB then, as now, had lots of them.

A month and half later, the Community Planning Group returned to the City Council and presented its ideas for the community-wide election, to be monitored by the League of Women Voters. City Hall—uncertain of what to make of this democratic metropolitan revolt—went along with the idea. And for awhile, it looked like the election would coincide with the November General Election of 1975—which gave activists hope for a large turn-out. But it wasn’t yet to be. It wasn’t quite time for OB to get its election.

The Effort to Derail the Election of the OB Planning Board

Back at home in OB, all wasn’t peace and happiness. A small group of conservative politicos, dissatisfied with the new Precise Plan, colluded on a strategy to derail the election. They went back to the City Council, complaining that the July 3 hearing had been “unfair,” and vehemently insisted that the City reopen hearings on the Precise Plan. This kicked the Plan back to the Council Rules Committee.

Who was this group? It had three key players; one was a very conservative former president of the OB Town Council who became notorious in 1972 for publicly denouncing demonstrators coming to OB and San Diego for protests planned for the Republican Convention—then coming to town but later moved to Miami. Next was an older, more reclusive extremist whose mother ran a breakfast cafe on Voltaire Street in OB. Both of these men wore a small silver hangman’s noose on a chain around their necks—the symbol of the Posse Comitatus—a group whose core belief holds that the elected sheriff in each county is the only true and rightful governmental authority. The third was another former president of the local town council. The three had managed to be selected as the leadership of an ad hoc coalition made up of Pen, Inc.—the originators of the Precise Plan—a sympathetic faction of the fractured Town Council, and the Merchants and Property Owners Association.

They sent out letters protesting the adoption of the new Plan, and complained that 2,700 property owners had not been adequately notified of the changes. They didn’t mention however that in fact all three had participated in the Committee of 16 and had been part of the process that they now criticized as being corrupt. Their maneuverings forced the City to hold additional meetings with the result being more delays in the implementation of the new OB Plan. On September 25, 1975, the City Attorney ruled that the City Council hearing on the OB Precise Plan on July 3rd of that year was fair and legal.

This didn’t stop the disgruntled dissidents. The three appeared in front of the City Council itself and demanded that it reopen its hearing. On October 16th the Council met on the issue and decided that the meeting of July 3 on the OB Plan had been fair; they refused to open up the hearing on it, and in effect, the Council passed the OB Precise Plan twice—once on July 3, and then again a second time when they validated their original vote. The three struck again. On December 11th, during a routine procedure to include the OB Precise Plan into the City General Plan, an attorney representing the ad hoc coalition sought a continuance on the grounds of their opposition to a Planned District. This caused even more delays.

Election Scheduled for Early May 1976

Finally the San Diego City Council set a date for the community-wide election of OB’s first planning committee: May 4, 1976. All residents, all property owners and all business owners could vote, and it would be monitored by the non-partisan League of Women Voters.

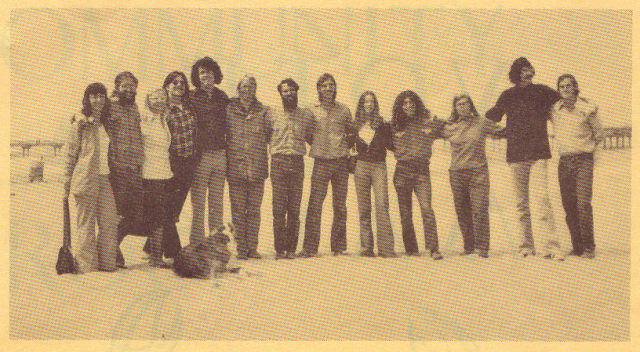

The Community Planning Group slate: from L to R: Maryann Zounes, Jerry Hildwine, Dolores Frank, Frank Gormlie, Lars Tollefson, Chris Bystrom, Ed Riel, Tom Kozden, Judy Czujko, Rich Cornish, Jill Mitchell, Doug Card, Phil Elsbree, (Norma Fragozo absent), and that’s Layla the dog at Gormlie’s feet.

The Community Planning Group spun into action and set up a process where local residents vied to be included on an organizational slate for the election. Out of a field of 35 candidates, 14 were elected as candidates to represent the group—including this writer. Internal discussions by the group resulted in a campaign platform that the official candidates had to endorse. This platform was very idealistic, very green, populist, and way ahead of its time.

The platform called the creation of the Planning Board “a step toward community self-government,” and that planning included things besides density limits and traffic designs, that “economic, social, political, environmental and cultural aspects . . . are just as important. In a word, people.” It stated community residents “should have the right to make decisions affecting all of their lives” which “includes public utilities, health care, the police and fire departments, social services, child care, educational and recreational resources.” Further, the platform set the context, stating that the group and its candidates:

see the fight for a decent plan and environment for Ocean Beach as a struggle between the vast majority of the people of the community, who are tenants, homeowners, and . . . small business people, versus the small group of wealthy elite who would like to turn our community into a playground and resort area for the rich.

It called for a system to funnel citizen complaints about city services, for staffing for the Board, declared “child care is a right” and that “health care is a right.” It called upon the Board to take measures to ensure a “balanced community” to include people of various income levels, of “different ethnic and racial backgrounds” and lifestyles. The platform stated:

“We believe that our society is suffering from its present degree of racial segregation. . . . We support efforts to increase the racial balance of the community. We endorse an effort to recognize cases of racial discrimination in the housing market and seek legal solutions as well as less formal community efforts to abolish this discrimination.

We recognize that many other communities in our society are having serious racial conflict, however, we feel that because of the more open and progressive atmosphere of Ocean Beach, this could be a community where people of diverse ethnic groups could live together “and build a real sense of community.”

These progressive views enunciated in the CPG platform of 1976 reflected the maturation of a grassroots movement that had evolved from protest to now projecting a vision for “community self-determination.”

These views, however, weren’t accepted by all, and once the campaign started, nasty edges emerged. A hate letter signed by “the Silent Majority of OB” circulated, denouncing the election and those involved. Fear-mongering rumors were heard that the radicals were taking over. Soon after, a slate opposed to CPG was formed, which included the president of the OB Merchants Association, a couple of prominent businessmen, a former City Councilman, and some property owners.

More roadblocks were thrown in front of the election. A lawsuit was filed a few months before, seeking an injunction against the entire election procedure. It was filed by none other than the same three who had earlier attempted to halt the Plan. The suit claimed that the City Planning Department had failed to send out adequate notices to all OB residents, property owners, and business licensees; it also asserted that residents and property owners who lived east of the community should also be able to vote—as they had an interest in the election. The City’s response was matter-of-fact: it used three mailing lists to ensure registered voters, property owners and business were notified, it put out multiple news releases on the election, and plastered dozens of posters around the community. The City made the point that residents throughout Point Loma and across town in the Clairemont neighborhood had an interest in the election, but they didn’t get to vote either. These were winning arguments, and the judge threw the lawsuit out. The last ditch effort to forestall the election and the Plan—the inevitable—was over. It was the end of the dreams for the commercialization of Ocean Beach—the final burial of the idea of turning the neighborhood into a mini-Miami Beach.

With finally all the obstacles removed, the election and the campaigning began in earnest. CPG candidates went door to door in their districts, distributing their individualized fliers and the group’s brochure. As it was an election close at home involving the very neighborhoods people lived in, interest seemed to be very high. Dozens of volunteers were enlisted and trained to manage the election, register voters, and prepare for the vote and its count. By the time election day rolled around, it had been ten months since the City Council had authorized it. And if anyone had imagined that the passage of time would wear down the level of activism in OB, they were sorely disappointed, as there was an emotional intensity cresting when May 4th, 1976 finally arrived.

The village had been divided into seven voting districts, with one to two voting sites per district, mainly in front of markets, large and small. The balloting took place all day—and at the appointed hour, ballot boxes were taken to the OB Recreation Center for counting, with everything monitored by the League of Women Voters.

When the votes came in, it was apparent that the election and its turnout had been astounding. Thousands had voted. All told, nearly 4,500 ballots were cast in this special election. With a community population of 13,000, the eligibility rolls included 6,100 registered voters, 2,100 property owners (1,100 inside the plan area and 1,000 outside the area), and 600 business license holders. In District 1 alone, 851 ballots were cast. 1,108 voted in District 2. District 3 had 755 votes. Another 1,085 voted in District 4—the business district (where this writer lost by 8 votes). The lowest turnout was in District 5—with 696 votes. These were stunning numbers.

The big news of the day: candidates from the Community Planning Group had captured eight of the 14 seats on the Board, a clear majority. Some of those elected had been involved since the beginning in the battle for OB’s community plan. They included a mix of Town Council types, counter-cultural radicals and anarchists, a “socialist,” professionals and small business people. The sweep by the planning group candidates was empowering and historic; a small neighborhood organization had grown to be the majority on the first planning board democratically elected in the city’s history.

After the first Board was sworn in, the members selected a woman activist as its first general chairperson, and then got down to the business of figuring out to how to proceed, how to operate. That Board and those that followed over the nearly four decades provide the modern history of development in Ocean Beach. By the time the first Board was installed in 1976, it had been a long, half-decade since the very first Precise Plan had been released in the summer of 1971. Over that time, there were numerous efforts by the establishment, through the city and its planning bureaucracy, to circumvent or out-maneuver the planning activists, to downplay their populism and demands for a democratic election. And all these moves were met with counter-moves by the activists that often upped the ante on the table.

When at the midpoint of 1975 City Hall finally authorized a democratic election by the community for its planning committee, the establishment had accepted the concept that ordinary working people, renters, small property owners and small businesspeople have a say in a community’s development and planning. This idea had been central to the grassroots activists during the entire lengthy battle for a community blueprint. And this is part of the legacy of the first planning board to all those that came later.

Stepping back, we can see that the creation of a planning review board for this small community back in the mid-Seventies was part of the “Revolt at the Coast”—a rebellion by residents up and down Southern California and San Diego, as quality-of-life issues became overwhelmingly paramount to unbridled urban development. The “Revolt at the Coast” included the passage of the signature environmental initiative of the time, the creation of the California Coastal Commission; it included the San Diego voter-initiated 30-foot height limit passed overwhelmingly by voters from all over the city—and enforced to this day. And it included the creation of the Ocean Beach community plan and its call for a democratically-elected planning committee—setting precedent for communities all over the city. When in 1976 the very first newly-elected Board for OB was installed, it also had the distinction of being the very first in the state of California.

The OB Planning Board Still Stands

A decade and half into the new century, the OB Planning Board still meets and is fully functional, reviewing projects, their setbacks, FARs, parking and height requirements, bulk and scale of houses, and whether they fit in with the character of the neighborhood. Since its inception, literally hundreds of OB residents, property owners and businesspeople have taken turns in the seats of the Planning Board—spending thousands of hours in keeping this grassroots, citizen-initiated, democratic institution and tradition alive. It is a testament to the people and character of Ocean Beach that the Board still lives, despite apathy, burn-out, construction upswings and economic downturns.

Over the years, there have been twists and turns, as interest and excitement over development issues have waned. Every decade seemed to bring its own mini-crisis, a push in the 1980s to raise density limits was defeated, a liberal anti-development slate won in the 1990s, attempts to build an Exxon gas station were quashed, and a progressive grassroots majority held sway for a few years in the early 2000s, even voting to oppose the Iraq war in 2003.

Ever since the very first planning committee was established in Ocean Beach, other neighborhoods within the city have organized their own, and in 2015 there are over 50 community planning committees. For instance, the very diverse community of City Heights had theirs organized in the early 1990s. And the planning committee for Barrio Logan was set up during the fall of 2014.

2014: The Showdown at City Council

And, nearly four decades after the OB Community Plan was established, in an ironic twist of history, its fate was again in question. The establishment—the powers that be—in the form of the San Diego Planning Commission, tried to undermine the essence of the Plan by eliminating a powerful tool the community used to maintain its working-class character. Thirty-nine years later to the month, the Community Plan of Ocean Beach was again in front of the San Diego City Council. It was July 1975 when the Council had originally approved the concept of the Plan and its Board—and it was in July 2014, when the Council again had choices to make on the OB Plan. The Council had to decide on whether to approve the Plan—again, albeit updated, but with its original restrictions intact, or accept the recommendations of the Planning Commission and gut the tool the OB Board utilized to inhibit over-development and keep some semblance of balance.

And likewise, a very similar “united front” assembled and mobilized at the City Council—similar to the one that had been organized in the summer of 1975 that had won the Council’s approval for their Plan. Now, all these years later, the residents of the exact same village, from tenants to merchants in a “sea of blue,” were again in a showdown with the city’s elite. The grassroots pressure had been tremendous, with even the Republican mayor coming out and publicly supporting the Plan. Thousands had signed petitions; the eloquence of community leaders that day in their deliveries before the elected officials was memorable. Tension mounted in the Chambers, as the time for the vote came due. Ed Harris, the Councilman who represented Ocean Beach made the motion to accept the Plan as is—without the Planning

Commission’s recommendations. Harris stated the Plan was about “putting lifestyle and community above profit” and that it was his “firm belief that the San Diego Planning Commission got it wrong. And we need to right it today.” Lori Zapf, the Councilwoman who would take over his seat a few months later, seconded the motion that day, and also praised OB, saying: “I think OB is the last authentic beach town in all Southern California.”

The final vote came down—it was all green lights on the video screen—it was unanimous—the entire City Council voted to approve the Plan as it was, without the recommended deletions; the Chambers erupted in yells, applause and whoops, with the clapping sustained for many minutes. Smiles flooded faces that had been tense just moments before. The joy among the blue shirts was indescribable but palatable.

Ocean Beach, that little neighborhood that hugs the coast, cliffs and hills of San Diego’s western peninsula had once again bucked the establishment—and had applied enough grassroots political pressure that the politicians were emboldened enough to go up against the powerful Planning Commission. The tools used by the community’s own local planners to keep some rein on overdevelopment for nearly four decades had not only been left intact but strengthened.

This decisive victory for community planners, their supporters and all the various groups that came out in support, the camaraderie and solidarity experienced over much of 2014, again had expression at the end of that year. The Town Council awarded the title of Grand Marshall of their annual Holiday Parade in December to the OB Community Plan, and coroneted the chief planning activist as “OB Citizen of the Year.” A contingent of fifty people holding signs walked at the front of the Parade as the Grand Marshall, to the applause of thousands who hugged the sidewalks along the main business street for the festive event. Once again, the OB Community Plan was celebrated.

The significance of these two parallel celebrated events, separated by 40 years, the original approval of a community plan for the community in 1975, and then the much more recent confirmation of the Plan and its celebration in 2014, cannot be understated. The story of how a small neighborhood resisted the plans of the establishment, not once but twice, in recent memory, cannot be a story that is lost because those who write history don’t want to tell it.

And within the larger story is the tale of how an organized group of community activists consistently fought for, demanded and mobilized for the right to hold democratic elections for the local planning committee, for the right of a neighborhood’s residents, even if they are renters, to take an equal part in the planning and development decisions that affect the neighborhood.

The small planning committee for Ocean Beach became of age when quality of life and grassroots democracy were the issues at hand. And this is the legacy that the OB Planning Board and all the community organizers who were involved in its creation leave to all other planning committees, across the city, and across the state. It’s a legacy that includes the story of how a small working-class community bucked the system, fought for democratic control, and saved itself by successfully beating back the plans of the establishment.

This story hasn’t made the history books and even city planners—suffering from an institutional amnesia—understate its importance to this day. But the stories of these two parallel movements—a generation apart—movements that saved this small working-class community—are etched like Native American petroglyphs on its sidewalks and in the social-memories of its elders.

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Cheers Frank, well done! I thank you for your bringing this story together and spanning the decades.

In the 10th paragraph you state: “Next was an older, more reclusive extremist whose mother ran a breakfast cafe on Voltaire Street in OB.”

Was that Lahoma, by any chance? I had a run in with them once and decided that family was nuts.

Rick

Thank you, Frank! It’s important the younger generation of OBceans to know and appreciate from whence OB came – a long and proud tradition of activism and civil disobedience for the public good.

Any plans to reprint this in a handy dandy booklet form?