Via See Columbia Travel

By Joseph Wagner / San Diego UrbDeZine

One crucial aspect of contemporary debates on spatial politics, socioeconomic stratification, and immigration is the issue of public transit.

Prior to the question of a person’s right to be in a city (or supposed lack thereof in the case of undocumented immigrants), there is the question of a city’s duty to provide feasible means for moving around in its space. Albeit mundane, it is a key factor determining a person’s economic and educational opportunities, to name only two.

And it hardly bears mentioning, but moving around in San Diego all but requires a car.

Although local officials could boast of the train (e.g., the SPRINTER in Escondido), a system of buses, trolleys, or even Uber pool, San Diego’s public-transit network imposes a logic of segregated spaces.

The “public” future of public transit is far from guaranteed. Per the report on the vision for 2050 published by San Diego’s Regional Planning Agency (SANDAG), the plan is to increase revenue from public-private partnerships fourfold over the next few decades. In fact, an explicit financial strategy in the report is to develop state and federal legislation to boost public-private partnership and incorporate greater private-sector funding of “public” transit.

Let’s say you grew up on my street in the suburb of Rancho Peñasquitos; from my house to the nearest Original Pancake House is 35 minutes by bicycle, 70 minutes by foot, or 45 minutes by public transit. Granted, this example is trivial: public-transit advocates are surely not in the business of ensuring suburbanites can access breakfast delights. However, it is illustrative, for a trip I have made on so many occasions, traversing a distance that seemed invisible from behind the steering wheel, would be truly burdensome by any other means.

Bicycle transportation, although laudable and effective in certain parts of the city, narrowly restricts one’s sphere of possibilities. There is an important emphasis on increasing bicycle mobility throughout San Diego, but there are distance obstacles making increased bicycle infrastructure alone insufficient. Unless you live close to San Diego Community College District’s (SDCCD) three main campuses, the notion of working part-time and pursuing a degree affordably is untenable. From my suburban street, getting to any SDCCD entails hours of bicycle riding or hours changing buses.

If we recognize that time is the scarcest of resources, bus, train, and bicycle are cost-prohibitive in San Diego. Sadly, the recognition of time as a scarce resource is something rarely done for the lowest income-garnering sectors; that is, for a salaried employee earning six figures, we do not balk at the idea that time is money. Yet, for an hourly wage worker whose time literally is converted into money, who is more likely to lose hours per day in transit to/from work, we can be quick to write off a 75-minute bus ride or an 8-hour shift lost to caring for a loved one.

In short, the message is that through an effective and humane engineering of public transit, we can engineer our social space. The predominant view of transit in San Diego is confined to cars; to wit, this mentality was baked into Southern California’s design, but the realities of a transnational city in the 21st century necessitate that we think otherwise.

Lauding how “walkable” Little Italy or Hillcrest is not the answer; developing a functioning downtown is a positive step, but does it represent a solution for the ideal of mixed socioeconomic neighborhoods? As is often the case in many areas of public policy (e.g., contraception), access is key. In the case of transit, access is achieved through infrastructure, not only in terms of developing better systems but also increasing trip frequency, adding new routes, increasing fare flexibility, improving systems for differently abled persons, etc. Going back to the SPRINTER, a light rail connecting Amtrak stations reinforces business commuters not using their cars—in itself admirable—yet fails to addresses the needs of commuters without a car.

It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the Internet provides sufficient access, that the Internet transcends physical barriers. However, for many communities, online access is one variable in a larger equation. In fact, online access is another barrier to transit here insofar as there is indeed complete information online (in a variety of languages) regarding San Diego’s bus and train system, but this information requires users to have an Internet access, know about the city’s Web site, and plan each trip with hours of foresight. Together, these requirements form an undue burden on people in marginalized communities. This burden is reproduced in our treatment of public space, as in the case of designing benches to prevent sleeping or “cleaning up” Balboa Park.

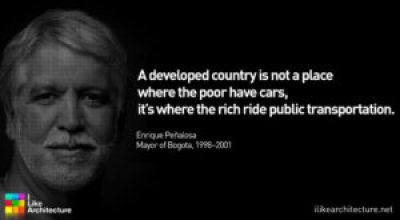

A clear framework for addressing this problem is captured by the mayor of Bogota, Colombia’s capital, the mark of civilization isn’t moving the poor in cars but rather moving the wealthy in public transit. If the city’s residents took this to heart, their social priorities would be reflected in a reconceived notion of people’s time and right to navigate around San Diego without a car in a timely and cost-effective fashion. In so doing, they would account for varied economic groups, social and educational “migrants,” and differently abled residents in an egalitarian and mutually enriching way.

A clear framework for addressing this problem is captured by the mayor of Bogota, Colombia’s capital, the mark of civilization isn’t moving the poor in cars but rather moving the wealthy in public transit. If the city’s residents took this to heart, their social priorities would be reflected in a reconceived notion of people’s time and right to navigate around San Diego without a car in a timely and cost-effective fashion. In so doing, they would account for varied economic groups, social and educational “migrants,” and differently abled residents in an egalitarian and mutually enriching way.

About Joseph Wagner: Born and raised in California, I accomplished my hippie parents’ dream of attending UC Berkeley, where I studied rhetoric. From there, I took off to Latin America, living in Argentina, Chile, and Colombia. In Colombia, I obtained a master’s degree in literature, focusing on literary history, literature and ethics, and the notion of comparative literature. Along the way, I have become a writer, editor, translator, and reader. I am drawn to issues of social justice, aesthetics, space, nonbinarism, all things language. However, these areas are bound by an education-centered approach: The more you learn, the more realize you don’t know. Although some consider it a platitude, I have integrated this approach into my life, and I continue to be guided by it.

{ 0 comments… add one now }