Other cities have sued over PCB pollution, but San Diego’s case is unique.

Other cities have sued over PCB pollution, but San Diego’s case is unique.

by Natasha Geiling / Think Progress / March 25, 2015

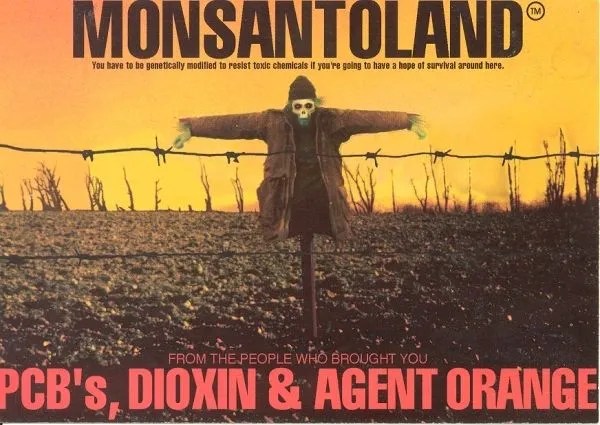

In a 1970 internal memo, agrochemical giant Monsanto alerted its development committee to a problem: Polychlorinated Biphenyls — known as PCBs — had been shown to be a highly toxic pollutant.

PCBs — sold under the common name Aroclor — were also huge business, raking in some $10 million in profits. Not wanting to lose all of these profits, Monsanto decided to continue its production of Aroclor while alerting its customers to its potentially adverse effects. Monsanto got out of the PCB business altogether in 1977 — two years before the chemicals were banned by the EPA — but just because the company no longer produces the toxic substances doesn’t mean it can forget about them completely.

Nor can the areas impacted by PCB pollution. On March 13, the city of San Diego, California filed a lawsuit against Monsanto for the company’s role in the production of PCBs.

“PCBs manufactured by Monsanto (specifically, Aroclor compounds 1254 and 1260) have been found in Bay sediments and water and have been identified in tissues of fish, lobsters, and other marine life in the Bay,” the suit reads.

“PCB contamination in and around the Bay affects all San Diegans and visitors who enjoy the Bay, who reasonably would be disturbed by the presence of a hazardous, banned substance in the sediment, water, and wildlife.”

Other cities have sued over PCB pollution, but San Diego’s case is unique. Other PCB-contaminated areas mostly fall under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 — better known as Superfund — a federal law meant to provide cleanup of the nation’s most polluted sites. But San Diego is using a claim of public nuisance to bring a case against Monsanto.

To Noah Sachs, professor of law at the University of Richmond and a scholar at the Center for Progressive Reform in Washington, D.C., the accusation of nuisance is what makes the San Diego case so interesting.

“What they’re saying is that there’s a product out there that is so dangerous that when it gets into the environment, it causes a nuisance by being there,” Sachs told ThinkProgress. “It’s certainly a novel lawsuit.”

PCBs are one of the most widely studied chemicals in the world, and considered one of the most toxic. In a 1998 report to Congress, the EPA listed PCBs as a probable human carcinogen, noting sufficient evidence from animal studies.

The report added that –

“PCBs also have significant ecological and human health effects other than cancer, including neurotoxicity, reproductive and developmental toxicity, immune system suppression, liver damage, skin irritation, and endocrine disruption.”

Produced mainly as a class of coolants and lubricants for electrical equipment — but used in everything from women’s shoes to flame proof Christmas trees — PCBs were largely introduced to the San Diego Bay after World War II, when wartime chemical companies refocused their attention on manufacturing chemicals for domestic use.

According to the complaint filed by San Diego, between 1935 to 1977, Monsanto was the only U.S. manufacturer to intentionally produce and sell PCBs for commercial use. The chemicals were so effective as fireproof coolants that they exploded onto the market — between the 1920s and their ban in 1979, some 1.5 billion tons of PCBs are estimated to have been used in manufacturing.

In early 1970s, scientists studying water pollution’s impact on mussels began to notice presence of the toxic chemical in the waters of the San Diego Bay. Cleanup efforts began, but were limited in their success, according to San Diego State University professor Richard Gersberg. PCBs are persistent organic pollutants that don’t break down easily in the environment — instead, they bioaccumulate, appearing in higher concentrations as they move up the food chain. A 1997 study of caribou in Canada’s Northwest territories found that they had levels of PCBs ten times higher than the lichen that they ate — and wolves that ate those caribou had PCB levels 60 times higher than the lichen.

In 2012, under pressure from water advocacy groups in San Diego, the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board ordered the cleanup of the polluted bay, giving the city of San Diego — as well as other industries involved in the dumping of PCBs — five years to dredge the toxic sediments out of the bay. Two years later, city agreed to pay nearly $1 million in fines relating to the dumping of PCBs, and also set aside some $6.5 million dedicated to cleaning up the Shipyards Sediment Site, a particularly polluted stretch of the Bay. But, as Gersberg notes, PCB pollution isn’t an issue limited to San Diego’s waters.

“PCB is fairly ubiquitous,” Gersberg told ThinkProgress, noting that the chemical can be found in waters all along the Pacific coast, from Vancouver Island to the Los Angeles harbor.

“[It] doesn’t come with a name on it, like ‘I’m from the Navy’ or ‘I’m from a gas and electric company.’”

San Diego isn’t the first city to sue Monsanto over its production of PCBs — the last three decades have seen lawsuits materialize in courts around the country. In 2003, Monsanto — along with its spinoff chemical company Solutia Inc. — agreed to pay $700 million to more than 20,000 residents of Anniston, AL to settle claims of PCB contamination, left over from a Monsanto-run chemical plant that operated in the town from 1929 to 1971. In St. Louis, another suit — claiming a link between PCBs and non-Hodgkin lymphoma — was allowed to move forward by a Missouri appeals court in 2013.

In the past, settlements from Monsanto in cases regarding PCBs have hinged on the company’s role in their disposal. The case in Anniston, for instance, ended when Monsanto conceded that much of the PCB pollution in the area was a result of improper disposal from their manufacturing plant. But San Diego’s case alleging that Monsanto’s manufacturing of PCBs was a public nuisance is different.

“If they were alleging that it was the company’s own disposal practices [that caused PCB pollution in the Bay], it would be a more straightforward and traditional case,” Robert Glicksman, professor of environmental law at George Washington University told ThinkProgress.

Though the case might not be traditional, it’s not without precedent.

“The analogy would be lawsuits against paint manufacturers for lead paint,” Rena Steinzor, professor at the University of Maryland School of Law and president of the Center for Progressive Reform, told ThinkProgress. Asbestos is another example of a toxic substance often cited in claims of public nuisance.

Public nuisance cases dealing with lead paint and asbestos have seen limited success across the United States, largely being denied by courts — with the exception of California. “One of the hotbeds for cities fighting back [against polluted sites] has historically been California,” Steinzor said.

In 2001, the county of Santa Clara filed a public nuisance suit against five of the largest manufacturers of lead paint, claiming that the companies had created a public nuisance by manufacturing and allowing the sale of a dangerous product. Though the first court to hear the case dismissed it, it eventually made its way to the California Court of Appeal, which ruled in 2006 that the case could move forward. In 2013, the case returned to the Santa Clara County Superior Court for trial — by that time, nine additional cities and counties, including the City of San Francisco and Los Angeles County, had joined the suit.

The suit faced bleak precedent elsewhere, as six states had previously heard public nuisance cases levied against lead paint manufacturers and had rejected all of them. In some cases, judges felt that the companies weren’t liable because the paint companies weren’t in control of the product when it had allegedly caused public harm — they manufactured it, but weren’t responsible for it once it left their hands.

In California, however, things went differently for the paint companies. Judge James Kleinberg, according to a review of the case by the law firm Morrison & Foerster, found that a company could be considered liable for having created a public nuisance if “companies had created or assisted in creating the nuisance by actively selling and promoting lead paint with actual or constructive knowledge about its health hazards.” In the end, three of the five companies were found liable and ordered to pay a $1.1 billion fine to assist in the clean-up of over 4.7 million California homes.

To Glicksman, Sachs, and Steinzor, Judge Kleinberg’s verdict creates an interesting precedent in the state for the case against Monsanto and PCB pollution.

“The plaintiffs will try to show Monsanto knew about the health impacts and that they knew it was getting into the environment,” Sachs explained. “Monsanto was the only manufacturers of PCBs, so that makes this lawsuit a lot easier. You don’t have to sort out who made it or where it came from.”

Monsanto, for its part, is distancing itself both from PCBs and its history of producing them. In a statement emailed to ThinkProgress, a Monsanto communications officer noted that, “Monsanto today, and for the last decade, has been focused solely on agriculture, but we share a name with a company that dates back to 1901. The former Monsanto was involved in a wide variety of businesses including the manufacture of PCBs.”

In 1997, Monsanto — which was founded in 1901 as a chemical company — shed its chemical background, spinning that sector of its business off into an independent company named Solutia. A 2008 Vanity Fair article notes that an oft-unspoken consequence of this separation is the ability for the new Monsanto, re-branded as an agriculture company, to “channel the bulk of the growing backlog of chemical lawsuits and liabilities onto Solutia. In 2008, however, Monsanto agreed “to assume financial responsibility for all litigation relating to property damage, personal injury, products liability or premises liability or other damages related to asbestos, PCB, dioxin, benzene, vinyl chloride and other chemicals manufactured before the Solutia Spin-off.”

Monsanto also stopped manufacturing PCBs after knowledge of their hazardous effects became relatively widespread — but internal company memorandums, like the one from 1970, imply that the company knew about the detrimental effects of PCBs at least by the mid-60s, if not earlier. Around that same time — with the release of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the subsequent scrutiny of DDT — PCBs began to fall out of public favor, as their deleterious environmental effects became more and more obvious. By 1979, the EPA had deemed them a banned chemical under the Toxic Substances Control Act (one of only five chemicals to be banned since the act became law).

Still, Monsanto denies that pollution related to the disposal of PCBs in the San Diego Bay is their responsibility.

“Monsanto is not responsible for the costs alleged in this matter,” the company said in a statement. “It only sold a lawful and useful product at the time, that was incorporated by third parties, including the Navy, into other useful products. If improper disposal or other improper uses allowed for necessary clean up costs, then these other third parties would bear responsibility for these costs.”

Both San Diego and Monsanto are in for a long fight, but if the city wins, the implications could be massive. “It would be a blockbuster verdict,” Sachs said, “the kind that could result in tens of billions of dollars of damages for Monsanto.”

But even a win for San Diego wouldn’t necessarily salve the widespread problem of PCB pollution. As a persistent organic pollutant, PCBs don’t degrade or break down in the environment — instead, they stick around in sediments and soils for years and can be easily spread through water and air. Most remediation techniques for PCB pollution involve dredging up contaminated sediment, a process that is both costly and, at times, inefficient.

“There’s no cheap way to do it, and since it’s … everywhere, even away from the hotspots, to really clean it up would be a massive undertaking,” Gersberg said.

{ 0 comments… add one now }