Editordude: Many who grew up at the coast in Southern California in the late fifties and early sixties remember how plentiful abalones were.Then they disappeared ostensibly from over-fishing. Yet, here’s some hope for their return.

Editordude: Many who grew up at the coast in Southern California in the late fifties and early sixties remember how plentiful abalones were.Then they disappeared ostensibly from over-fishing. Yet, here’s some hope for their return.

By Laylan Connelly / Southern California News Group / July 19, 2018

John Warren thinks back to the days when getting his hands on abalone was as easy as jumping on a surfboard and plucking the plentiful shellfish off a reef.

Warren, who grew up in Capo Beach, always cooked them with white wine in a big wok for the “ab feed,” when friends gathered to tell stories and eat their catch of abalone, lobster and fish straight to the pot from the sea.

“Many of us learned to dive just because of abalone,” said Warren, now 72, of his memories from the ’50s and ’60s. “When the water was clear, you could look down and see them from the surface and dive down and pull them off with your hands. They were very abundant.”

Those days are gone, and the memories of that era are fading away after over-fishing nearly wiped out the existence of abalone.

Yet one woman is trying to not only keep the stories of California’s coastal culture alive, but to restore the abalone population back to healthy levels .

“We have to start remembering it,” said Nancy Caruso, a marine biologist and founder of the non-profit Get Inspired. “We have to remind people what we had.”

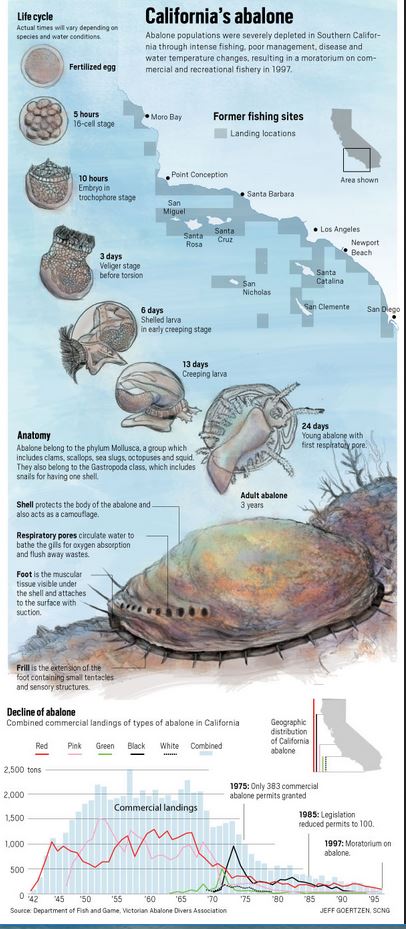

Abalone has a storied history in California. Seven different species thrived in the waters off the state’s beaches. Shells dating back thousands of years were found at early Native American sites, used in trade for other goods, Caruso said.

When Chinese immigrants came to California in the 1920s, they’d eat the familiar fare, which also grows off the coast of Asia. Japanese immigrants started harvesting them, an easy task for a culture known for their free-diving skills.

“They were getting the different species in deeper depths,” Caruso said.

It was at the turn of the century, after rave reviews of an abalone dish prepared at a Monterey restaurant by “Pop” Ernest Doelter, dubbed the “Abalone King,” that the American masses began devouring the shellfish, spawning the commercial abalone diving industry, she said.

The catch limits set by the government at the time showed how plentiful they once were: Divers could take 120 dozen, or 1,440 per day, Caruso said.

“I have pictures of piles and piles of shells outside of the processing plants, from San Diego to Morro Bay, 20 feet high,” she said.

During World War II, abalone was canned and sent to soldiers. At local fish markets dotting the coast, abalone sandwiches were a popular menu item.

But by the ’70s, there was a huge, noticeable decline due to over-fishing, causing prices to go up as supply went down.

In the ’80s, a sabellid polychaete worm wreaked more destruction after it was introduced to California’s abalone farms from South Africa, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The worms, which live in tubes within the abalone shell, cause severe shell deformities making them prone to breakage and resulting in slow growth.

At the same time, Withering Syndrome severely impacted the wild abalone population, a disease that shrunk the foot muscle of all seven California species.

Then various environmental circumstances caused kelp, their food source, to disappear. The abalone starved.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that Southern California fisheries banned catching abalone, but “it was too late by then,” Caruso said.

The last red abalone fishery on California’s northern coast closed in December 2017 after restrictions from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife because of concerns about the recent lack of kelp.

“Until last year, you could still take abalone (from) there,” Caruso said. “But they are losing their kelp, so the abalones are dying.”

‘Ab feed’ revival

On Friday, July 13, about 40 people gathered for an “ab feed” to eat red abalone from The Cultured Abalone Farm in Goleta.

The abalone was prepared by the Cannery Restaurant in Newport Beach, chefs lightly breading the palm-size fish before frying it.

The ab feed was the brainchild of Spencer Croul, co-founder of the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente, who told Caruso about the gatherings once popular along California’s coast when she started the Green Abalone Restoration Project six years ago.

Caruso hoped the ab feed will become an annual event to share stories of decades ago, and to continue interest and fundraising for Get Inspired’s Green Abalone Restoration Project.

“We’ve forgotten how much we loved them,” she said, holding up big, empty shells. “We’ve forgotten how much they used to be part of our culture.”

The goal of the Green Abalone Restoration Project is to grow 100,000 abalone in ten years, and to plant them along the southern California coastline.

Get Inspired was issued the first abalone restocking permit in 20 years. If successful, the project would be one of the largest endeavors to restore an ocean animal, according to the project’s website.

The Cultured Abalone Farm is where Caruso is hoping her broodstock will multiply. She’s made arrangements with schools and marine organizations to grow abalone in classrooms and aquariums around Southern California before she can place them into the ocean to repopulate. In the next decade, an estimated 40,000 students will grow the abalone in their classrooms.

But the undertaking will take patience as the sea creatures slowly grow.

Caruso showed images of the 91 abalone that survived the first spawn at the farm about a year and a half ago. After a year, they grew to the size of a thumbnail.

To date, 39 have survived.

“Want to see the pictures of my babies?” she said, with the tone of a proud mother. “The amount of money and time I’ve put into them, those are my children.”

Protections

Caruso’s surviving abalone – adorned with bright pink tags – are being cared for at the Ocean Institute in Dana Point and at the Pennington Marine Science Center on Catalina, spending the summer at the aquariums until school resumes and students take over.

Caruso will teach them how to run the tanks, grow bacteria to process waste and feed the young abalone.

Ocean Institute marine biologist Julianne Steers has been helping with the project since the start. She watches over a group of 20 young green abalone, along with a few larger red abalone, tucked in a tank where they munch pieces of kelp. She recently measured the green algae toddlers; they are growing.

Studies show they will need to be grown for about five to seven years, about the size of a palm, before they can return to the ocean, Steers said. Earlier efforts with young abalone about one inch in size weren’t successful.

“They basically are food at that point,” Steers said. “Whatever effort you put in, time you put in … they just became Scooby snacks.”

Steers said more is needed to inform the public about abalone, and the laws that exist to protect them.

“Even though there are warning signs and they have their protections, many of them are endangered or threatened species,” she said. “People just unknowingly collect them, which is illegal now – that’s poaching.”

Steers said it’s not just the lives of abalone that will be impacted with the restoration project.

“They also hold a nice niche in the ecosystem and provide a balance,” she said. “They too become food for sea otters and sheephead and other organisms that are key to this wonderful environment we have.”

Hopes for the future

Caruso still sees large abalone occasionally off the coast – but those may be 20 years old, lucky enough to survive mankind’s purge.

What she wants to see are the babies, smaller ones that hint of abalone reproduction off local waters – the first signs of a rebound since protections were put in place. So far, she’s not seeing them.

But their food, kelp, has returned thanks to the Giant Kelp Restoration Project started in 2002 by the Santa Monica-based Bay Foundation. With the help of 10,000 students who helped grow and replant the kelp forests off Newport Beach to Dana Point, they are flourishing fifteen years later.

Caruso hopes the kelp will allow the abalone she’s growing to have abundant food to thrive.

“We’re growing babies, and the idea is to grow them out here,” Caruso said to the crowd at the beach Friday. “And who knows, maybe in 30 years you’ll be able to go out here and properly harvest abalone for a real ab feed.”

{ 6 comments… read them below or add one }

I got my diving certification in Monterrey back in 1975 and I dove all up and won the north coast. But, when we dove for abalone, we were not allowed to use scuba gear, you had to free dive. Free diving in that cold water, 15-25 feet deep with strong surges made getting your small limit a real ordeal. I’m pretty sure I’d have a hard time doing it again. But, it made sense because it made getting them hard and there was small limit, both of which protected the population. In 1977, I moved here and learned that there were several varieties of abalone in these waters, Up north, it was mostly big red abalone. What surprised me was that you could use scuba gear to dive for them here and that just seemed like a bad idea to me. I don’t know how much that difference contributed to the decline but I’m sure it had an effect along with the other things cited in this story. I used to spear fish and collect scallops but I quickly realized the ocean would be cleaned out if that continued, so I stopped taking anything. The ocean looks mighty but the hand of man is mightier, maybe it’s time to do some good instead of harm.

I remember in the seventies going to the Red Sail to have Abalone dinner for 10 bucks, long gone sadly.

Yep….the Red Sails Abalone sandwich for lunch!

Abalone farms in Baja, Mexico are trying to raise sustainable stock but they take decades to grow to the size of a human hand. These ancient creatures were over harvested in the early 1900’s for food and shell ashtrays. Google “Abalone shell piles” to see the California destruction of this resource. Today they are protected in U.S. coastal waters. With any luck maybe science can bring them back faster and healthier than before.

I remember being about 7 and my uncle taking me out to hunt abalone back in the late 60’s. I’d sit on the rocks waiting while he dove down and came up with a few abalone. He did use the shells for ashtrays. We were all sold clueless about what we were doing to the environment back then. Sad that they’re now gone.

I was a SoCal Commercial AB Diver in the early to mid 70’s, REQUIRED to dive with “surface supplied air” (a compressor to a 500′ hose, connected to a regulator) Diving the outside of Catalina until they became scarce then move out to San Clemente Island along with a couple of trips to the Outer Bank. The reason I quit, poachers. If I picked ONE AB that didn’t measure (a short) by even a fraction of an inch, Fish & Game would take my license AND the entire catch (people remember watching Crab fishing in the Bering Sea?) same for them. If they didn’t measure, we had to place them back EXACTLY where we found them!! Ensuring NEXT year it might be legal and keep the fishery producing. Poachers and the PEOPLE who bought from them, have NONE of these worries or for that matter even CARE. The day I stopped I cried, because I saw what was going to happen and could do nothing to stop it. Think of Elephant/Ivory for a comparison. It’s all about GREED~~