California should require developers to include affordable housing for a fifth of all new projects

By

As the economy improves, California’s affordable housing crisis is worsening. The average rent in California ($1,240) is almost fifty percent higher than the national average. This is pricing out our state’s low-wage blue collar workers, who have flat incomes and rising commutes. It would take a service worker in San Jose 20 years to save up enough to buy a home.

Unfortunately, government programs that help developers build affordable housing have barely met a fraction of the need. These programs provide financial incentives such as tax credits, grants and below-market loans to developers in exchange for keeping rents below market. However, the state’s Legislative Analyst’s Office found that these programs together have subsidized the new construction of about 7,000 rental units annually in the state—or about 5 percent of total public and private housing construction—since the mid-1980s.

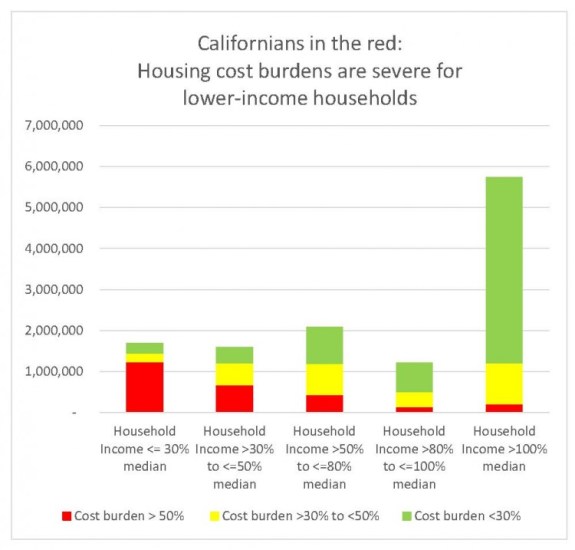

California has to rely on private developers for providing affordable housing, since there are only about 44 thousand public housing units. However, out of the entire stock of 5.7 million rental apartments in California, about half a million have been covered by these programs; and for many projects benefiting from public subsidies, they are at-risk of reverting to market-rate or have already been converted.

In response, California lawmakers are proposing an expansion of tax credits and low-interest loans, and regulators are mulling the removal of caps to developer fees. No doubt these would create additional incentives for developers to generate more affordable housing.

However, this begs the question of whether California’s “carrot” approach of luring developers with financial incentives is sufficient?

Developers and landlords are getting a free-ride, and are benefiting from California’s housing crisis for several reasons. First, the largest bump in housing costs come from land value, which benefits existing landlords and speculative investors. Second, we saw a lost decade in apartment construction when rents were rising even when home prices were falling. And finally, when housing construction did resume, developers are building pricier products rather than entry-level homes that are much in need.

These apparent market anomalies all point to the lack of state regulatory oversight over the housing market in California.

For example, more developers in San Diego downtown are paying a fee in lieu of including onsite affordable housing. During the era of redevelopment, there was a state-mandated requirement to produce 15% of the units to be affordable to low- and very low-income households.Redevelopment agencies across the state created 63,000 new affordable housing units during FY2001-2008. Despite their accomplishments, only 11 percent of the funds set-aside for housing was actually spent on housing (state requirement was 20 percent).

Thus, even when the incentives were available, developers and local jurisdictions did not produce enough affordable housing. Now, many coastal downtowns in California that were previously subject to affordable housing set-asides and productions goals, are at-risk of becoming exclusive domains of only those who can afford it.

Developers claim that increased supply, in and of itself, will increase affordability. An associated theory of “filtration” is that as the rich buy more expensive new homes, they churn their old homes over to the less rich, and so on, until it trickles down to the poor. In reality, California’s leave-it-up-to-developers policy has failed to produce results because of innumerable imperfections in the “free market” for housing. Filtration only works if there is upward mobility, but there has barely been any upward mobility of the lower and middle-income groups in the last few decades.

So the rich increase their concentration of wealth by investing in multiple properties as they appreciate, while renters are still struggling with student debt, facing significant credit barriers to enter the for-sale market. Foreign investors can cloak themselves within the opacity of the real estate in luxury high-rises, while a new home-buyer struggles with limited inventory and stricter lending criteria for mortgages.

Where a few large-scale developers can control pricing/rents of new homes/apartments in a market, the individual buyer/renter has little bargaining power. This is compounded by the fact that land value itself is a derivative of government zoning and regulation, so by increasing entitlements, the government is directly boosting land values. Most working people are constrained by the location of their jobs, are not free to choose where they can live, and are therefore fleeced by rent-seeking landlords and speculators.

Therefore, there needs to be a statewide inclusionary mandate of 20 percent of all new housing (rental and for-sale) to be affordable to low-income families. Here are some approaches that could implement the state mandate at a local level:

Therefore, there needs to be a statewide inclusionary mandate of 20 percent of all new housing (rental and for-sale) to be affordable to low-income families. Here are some approaches that could implement the state mandate at a local level:

- Enforcement of the regional housing needs: The state allocates a share of each region’s housing needs to regional governments which subsequently allocate them to local jurisdictions. This is mainly a planning exercise on paper, and regional governments need to be held accountable for the actual production of affordable housing on the ground.

- State intervention for federally subsidized at-risk housing: The state must institute a “right of first refusal” or similar measure to allow housing authorities to purchase housing with expiring covenants, or offer a subsidy program for landlords that want to continue affordability.

- Rent stabilization and housing assistance to households: Almost 400 thousand California households benefit from housing assistance. About 15 California cities have some form of rent stabilization, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland. These programs need to be augmented through innovative programs like incentive zoning.

- Goal of eliminating homelessness region-by-region: The fragmented approach to dealing with homelessness results from the bifurcation of responsibilities between cities and counties. Cities are primarily concerned with safety and streets, whereas counties are concerned with services and shelter. The state needs to provide direction and resources at a regional level, so that homelessness is eliminated, not displaced. Rent subsidies to house the homeless are considered the most effective, and they must be paired with willing landlords through local controls.

- Economic development tied to housing production: The housing industry needs to be reformed so that the jobs created in construction are not low-wage jobs that themselves create a demand for subsidized housing. Moreover, wages in the service industries also need to catch-up with the increased cost of housing. A San Francisco study found that for every 100 market rate condominium units built, there are 25 lower income households generatedthrough the direct impact of the consumption of the condominium buyers and a total of 43 households if total direct, indirect, and induced impacts are counted in the analysis.

My recommendation of a statewide affordable housing mandate does not preclude additional incentives, such as community benefit zoning. Rather, much-needed state resources and a federal National Housing Trust Fund must be adopted to fund the actual production of the affordable housing.

However, market-rate developers in California have no reason to build below-market-rate housing. It does not make economic sense. Here is how Oliver Wainwright from The Guardian recently explained the lack of production of affordable housing in London:

“No developer, it seems, is immune from exploiting whatever the system allows them to get away with…Many developers imply that building affordable housing always entails a loss – but when affordable rents are capitalized at up to 80% of market rate, the reality is it just makes less of a profit. (Affordable housing also removes a chunk of the development risk, given it comes with guaranteed funding from a housing association.) Still, with an imperative to maximize shareholders’ returns, why would any commercial developer agree to anything that makes less profit than the maximum that can possibly be squeezed out?”

Developers will continue to exploit the toothless planning system in California to minimize affordable housing and maximize profits, unless they are required to play by a different set of rules. This different set of rules has been recently validated by the California Supreme Court, in San Jose’s inclusionary housing law.

In this case, developers of new construction over 20 units were required to sell at least 15% of the units at affordable prices. Developers challenged the law as an unconstitutional exaction that needed to be justified by the project’s own impacts. The Supreme Court unanimously decided that the affordability mandate is really a condition on use of the land, and the government can regulate uses the same way as they can regulate density and heights. Here is an excerpt:

“In any event, it is well established that the fact that a land use regulation may diminish the market value that the property would command in the absence of the regulation — i.e., that the regulation reduces the money that the property owner can obtain upon sale of the property — does not constitute a taking of the diminished value of the property. Most land use regulations or restrictions reduce the value of property; in this regard the affordable housing requirement at issue here is no different from limitations on density, unit size, number of bedrooms, required set-backs, or building heights.”

Inclusionary housing creates balanced communities with enhanced economic opportunity for lower-income families to escape a cycle of poverty. There is no more compelling economic interest for the state today, than the fact that it is too expensive for our workforce to live here. Therefore, the state of California should require developers to include affordable housing for a fifth of all new projects.

Murtaza H. Baxamusa, Ph.D., AICP is a certified planner, writer and thinker. He develops affordable housing for the San Diego Building Trades Family Housing Corporation, and teaches urban planning at the University of Southern California (USC).

{ 0 comments… add one now }