Last night’s wonderful trip down OB memory lane was enjoyable to a standing room only crowd at the OB Historical Society‘s monthly event.

Last night’s wonderful trip down OB memory lane was enjoyable to a standing room only crowd at the OB Historical Society‘s monthly event.

Led by Kathy Blavatt and her half hour slide show, we were presented with the history of the “Collier Parkland” – where the prominent and colorful Charles Collier gave away 60 acres to Ocean Beach “for the children of San Diego” 105 years ago. Carefully explaining to the audience at the Methodist Church community room on Sunset Cliffs Blvd, Kathy laid out in long-lost old news clippings and photos how those 60 acres were carved up over time by the City, the voters and other factors.

Voters approved a school on the parkland – originally called “Collier Jr High”, now Corriera Middle School -; the YMCA came in, a church followed, the boulevard named Nimitz was carved out of Masaka Canyon – a street original put in by Collier, and finally Cleator ball-field was developed on the north side of Nimitz.

Meanwhile on the south side, the City planned to sell off the entire section. In the early 1970s, OBceans and their Point Loma allies pressured the City to allow a park to be developed. This “pressure” lasted years and included the late March 1971 Collier Park Riot.

Last night has inspired us to repost the following:

OB’s True Founder: Charles Collier

Editor: The following was originally Part Four of the series on “What is the true birthday of OB and who is its true founder?” written in September 2012 (Here are Parts One, Two, and Three.)

Besides J.M. DePuy and the partners Billy Carlson and Frank Higgins, there’s another historical character who walked across Ocean Beach’s stage, who had such an effect on the development of the community that some consider him the “true founder” of the village. And that is Col. David Charles Collier – who Collier Park up in northeast OB is named after.

Although Collier came later than our main contender for the title of the community’s “father” – William “Smiling Billy” Carlson, he had as much to do with what turned into our little town by the sea as anyone else. And perhaps more so.

“Charlie” Collier’s Story

Ocean Beach and Col DC Collier first intersected in 1887, when young “Charlie” – then only 16 – bought one of Billy Carlson’s lots in Ocean Beach. The lot was close to the cliffs, over on Pacific – now Coronado Avenue – and Bacon Street. Of course, as a youth – he probably was backed by his father, DC Collier, Senior – a lawyer and former judge from Colorado.

Charlie Collier at first built a shack on the property – which had quite an ocean view – and over the years, added to it until it was a mini-resort on the cliffs. He and his family lived there for decades.

Priscilla McCoy and Sally West discussed this in their essay:

“Among the families that camped on the beach [at Ocean Beach] was that of D.C. Collier Sr., who had been enjoying beach outings since moving to San Diego in 1884. The son, David Charles Collier, then 16 years old, bought one of the very earliest lots sold by Carlson, at ‘Alligator Rock’ (now Ocean Front at Bacon and Coronado). He built a shack or shelter for camping expeditions.”

Ruth Varney Held – OB’s original historian – also described the purchase.

“He called it ‘Alligator Rock Lodge.’ If you go to the beach there at very low tide, you can look up at ‘the rocks’ and see black areas of sandstone. No doubt old D.C. found one that looked to him like an alligator.”

The Collier family had arrived in San Diego only two years before that real estate purchase. They arrived by way of steamship, and disembarked at the 5th Avenue pier. Charlie’s family was from Central City, Colorado, where he was born in 1871, to Martha and David Sr.

Collier Senior had made a name for himself back in Colorado as lawyer, judge and newspaper man. Despite this apparent success, the couple decided to take the family farther out west, and in 1884 moved young Charles and his two siblings to San Diego. They ventured upon these shores during Southern California “boom” years, and dug in roots. Senior built the family a house on Sixth Street and within 5 years had become partner in a prestigious law firm.

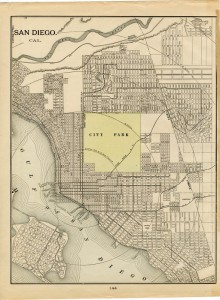

In the meantime, Charlie had a series of small-time jobs: janitor, messenger boy, and book keeper at a bank while he finished his public schooling at Russ High School. The school was on the edge of what was then called City Park – and what later would become Balboa Park. As he found shade and solace under the park’s trees, he had no idea that someday he would be responsible for re-naming the park. At the age of 20, Collier passed the state bar exam and went to work in his father’s office as a lawyer. Upon the old man’s death in 1899, David began moving up the local attorney ladder.

Charles’s movement up the ladder is definitely reflected in his first marriage. In 1896 Collier married Ella May Copley, whose brother was Congressman Ira Copley from Illinois, and who ended up buying both the San Diego Union and Evening Tribune. Collier, apparently, had sufficient connections and pedigree to warrant this marriage into the elites of San Diego. Nevertheless, Ella and David had two sons and stayed married for 18 years. The family lived at “Alligator Rock” in Ocean Beach for many years, which gained a Japanese Garden and bathing pool, and where they entertained many celebrity guests.

Charles’s movement up the ladder is definitely reflected in his first marriage. In 1896 Collier married Ella May Copley, whose brother was Congressman Ira Copley from Illinois, and who ended up buying both the San Diego Union and Evening Tribune. Collier, apparently, had sufficient connections and pedigree to warrant this marriage into the elites of San Diego. Nevertheless, Ella and David had two sons and stayed married for 18 years. The family lived at “Alligator Rock” in Ocean Beach for many years, which gained a Japanese Garden and bathing pool, and where they entertained many celebrity guests.

Following the boom came the “bust” years of the late Eighties. Many of Collier’s clients couldn’t pay him for his legal services in cash, so they would pay him with deeds to what they considered worthless properties – real estate that they had acquired during the good years. Collier accumulated the properties, and then began sub-dividing the plots, laying out streets, installing utilities, and planting trees. In 1904, he formed the Ralston Realty Company and began selling lots.

Northeast Ocean Beach – early twentieth century. (Note bridge to Mission Beach and Abbott Street market.)

While Collier lived at Alligator Lodge in OB, he began selling all these lots that he had collected – and they were in OB, Point Loma, PB, Normal Heights, North Park, University Heights, and other areas – including La Mesa and Ramona. Collier had truly become a developer – and by 1909 had established the firm, D.C. Collier and Company to manage the properties.

Collier’s Railroad Comes and Changes OB

Then he made something happen that totally changed OB’s relationship with the rest of the world. In order to increase access to his sub-divisions in OB and Point Loma, he built a railway and called it the Point Loma Railroad.

As told by Ruth Held, Charlie Collier saw a need for a trolley line out to Ocean Beach, much like those already operating to National City and Old Town.

“He dreamed up a neat route for it, bought the lots for the roadbed, and in 1907 started building. By May 1909, it was ready, and 250 of San Diego’s big-wigs came to the great party, the inaugural ride.

All four cars of the new line were hitched up at the downtown plaza. Charles turned on the current, the City Guard Band played, and off they went.”

This is somewhat reminiscent of Billy Carlson’s attempt at building a rail line to Ocean Beach back in 1888, although Carlson’s was much more of an ill-fated venture. Ruth Held continues the ride:

“They sped out to Dutch Flats (now Barnett Avenue), down Rosecrans, up to Voltaire and south again on Bacon. They got off at Niagara Street and had refreshments and speeches; they yelled, ‘Good boy, Charlie,’ and strolled over to his Alligator Rock Lodge to continue the festivities.”

Held sums it up:

“The trolley was a huge success, and by 1910 Collier had lots of company; there were 100 houses in OB by then. You can still see traces of tracks on Santa Cruz.”

In comparison, there were only 18 houses in OB just two years earlier. Details of Collier’s OB developments are detailed by McCoy and West:

“In 1908, the office changed to the D.C. Collier Company. … He opened the tract Ocean Beach Park just north of the Carlson Ocean Beach, from Brighton to West Point Loma Blvd. and east, to the Dupuy [sic – “DePuy”] Addition on Seaside, then to Wabaska Canyon (now Nimitz).

Voltaire and West Point Loma were planned as wide access streets. Lots on the narrow streets were offered in different size and configurations, but all small and intended for vacation dwellings. … He graded and paved streets, brought in utilities, and built a trolley line, which became part of Spreckels’s City trolley system.”

Once the new trolley line was established, what was to became the village of Ocean Beach got a kick in the ol’ proverbial pants. This significant access made it possible to have a community connected to the larger and growing metropolitan area of San Diego.

Collier’s successful streetcar line was the turning point for Ocean Beach. San Diegans now could live at the beach and work or go downtown – as access to Coronado was limited.

Ruth Held analyzed it:

“… In 1909, Col. D.C. Collier gave us a good streetcar line that made OB possible. For the first time people could work in downtown San Diego and live by the ocean.”

May 1, 1909, was the day the Point Loma Electric Railway really started OB. So now, in 1994 [ed: year Ruth Held wrote the essay], we have Streetcar Day to celebrate our 85th birthday.” (Our emphasis.)

What happened after the railway line was opened is described by McCoy and West:

What happened after the railway line was opened is described by McCoy and West:

“The opening of the trolley line in 1909 produced a rush of lot purchases, as well as a boardwalk the length of the beach, the cotton candy and games of chance style amusements, and ‘thousands’ of seaside visitors. Real estate excursions came from all points east and from Los Angeles. … One source notes 100 houses built by 1910. “

But selling lots and building railway lines weren’t the only thingsl that Collier did in Ocean Beach. In 1909-10, he had built with his funds a two-room school for the community, calling it the Ocean Beach School.

At some point, Collier also donated land for a park in Ocean Beach – what is now referred to as “Collier Park”, situated as a L-shaped plot bordered by Greene and Soto Streets north of Voltaire in northeast OB. It was originally much larger and included additional land across Wabaska Canyon (now Nimitz). Collier also built the road through the park. Of course, now that portion of the original Collier Park in Point Loma has been taken over by the YMCA, Correia Middle School, a church, and what’s left is called Cleator Community Park, essentially a kids’ ballpark.

Collier Outside Ocean Beach

Naturally, Col. DC Collier had a life outside Ocean Beach (the “colonel” was a title of honorarium bestowed on him by a California governor) and he drove a wide path of civic involvement in the larger metropol known as San Diego. (A year-by-year accounting of Collier’s affairs and involvements are beyond the scope of this historical accounting of the possible contenders for the title of OB’s “founder”, but we will tag the more noteworthy events.)

Researcher and historian Richard Amero has written a great overview of Collier’s life in San Diego for the San Diego History Center. Amero called Collier “one of San Diego’s best known characters at the turn of the twentieth century.”

“He had a strapping figure, a leonine mane of hair, and flamboyant clothes. After returning from a visit to Brazil in 1912, he appeared at public meetings booted and spurred, with a striped poncho made of alpaca hair, a wide belt with knife attached, and an enormous sombrero on his head. He most often wore a five-gallon Stetson hat, … and a Windsor tie, ….”

Collier sounds a lot like the denizens of OB who have lived there since the Sixties. Yet not only did Collier take on leading roles in the greater San Diego community over the decades as a financier, developer, philanthropist, and civic activist, he also owned the first phonograph in San Diego – a Berliner Gramophone, and the first automobile – an Oldsmobile that could go up to 25 mph, and travel 50 miles on 3 quarts of gas. (How far does your current car take you on one gallon of today’s gas?)

With his real estate successes, Collier expanded his holdings. In 1900, he bought mines up in the Julian area. Five years later he bought into a land and water company in Ramona, eventually building a secluded, second home in the Bellena area. This is why there’s a park in eastern Ramona today. Charles built another house and chicken farm in the La Mesa Springs area in 1907 – and this is probably why there is also today a Collier Park in La Mesa.

The Politics of Water and the Progressives

The politics of water in San Diego have always been – obviously – of enormous concern to whoever lives in the region. Who was to serve water to the good citizens of San Diego was a huge issue at the turn of the twentieth century – and it had been an ongoing civic conflict and had been for years over which company would sell their aqua-system to the city. And Collier got caught up in the conflicts.

On one side stood the water company that had built a flume system from Cuyamaca Reservoir and its political allies, and on the other side, stood the company that built a system involving dams in the Otay area and its influential friends and supporters. A few years earlier, we saw how Billy Carlson – then mayor – became victimized by the warring factions.

Mr. San Diego of that era, ol’ John D Spreckels – our own robber baron – owned railways and utilities and properties all over San Diego and exerted huge influence on most, if not all, civic issues. Spreckels owned the Southern California Mountain Water Company – the Otay water system. Collier helped persuade the City Council in 1905 to override then Mayor John Sehon’s veto that had blocked the city from buying water from Spreckels. From then on, Collier and Sehon feuded. At the time, Sehon was also fighting with Spreckels through rival newspapers – and he was opposed to anything to do with the financial giant.

Three years later, Collier and Sehon had a public yelling contest. During a political meeting at a theater that Collier owned, Sehon – the former mayor – got up to make an unscheduled speech. Collier rose up to protest this – with his reported quick-temper getting the best of him. And the yelling began.

Later, the two switched sides, in a sense. Gradually, Collier grew distant politically from the old-line Republicans who ran the local and state-wide party, and joined the Progressives – a wing that was challenging the old guard. Locally in San Diego, this meant going up against Spreckels and his friends and in turn supporting the Progressive opponents – like George Marston.

During San Diego’s infamous Free Speech Fight of 1912, Spreckels led the official and vigilante crack-down on the Wobblies and their supporters. During this period, the police were used in efforts to squelch free speech rallies, and who was the superintendent of police – the main civilian over the police chief? It was John Sehon. Doubtless, he was dutifully pulling the strings of repression. George Marston – meantime – and his progressive and civil libertarian allies – opposed the crack-down. Collier was his ally. And in fact, in 1916 when Collier ran for city council, he lost primarily due to his close associations with Marston.

Col. Collier got around, and definitely traveled among the ruling elite of San Diego. While president of the city’s Chamber of Commerce in 1908, he organized a huge reception for President Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet – which was a fairly naked effort to get the Navy to dredge shallow San Diego Bay. He also served on the staff of California State Governor JN Gillett for several years.

In 1910, Collier organized the Aero Club of San Diego and became its president. He recruited a well-known aviator to set up a school on North Island. Over the next few years, the Curtis School of Aviation churned out fliers who set world records in bi-planes. By 1913 North Island had become famous for one of the best aviation fields in the country – and this in turn eventually led to the Navy setting up a base and airfield at the site.

Over at the city’s waterfront, legal developments were occurring that would allow the tidelands to be used by municipalities. For two years, Collier worked to obtain legislation at the state level using his Sacramento contacts that allowed San Diego title to its shores from National City to Point Loma. This legislation gave, according to a contemporary observer, “to the city of San Diego title to its tide lands, which are the basis for our present water front and harbor development.”

The Panama-California Exposition

Hands-down, Collier’s greatest achievement – outside of helping to establish the village of Ocean Beach – was being in the civic leadership of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. From 1909 to 1912 he was its Director-General, and from 1912-14 its President.

Collier served without pay, covered his own expenses, as he lobbied in Washington DC for government support and traveled to South America and Europe on promotional jaunts for the Expo. He gave $50o,000 of his own money to the project (that was a heck of a lotta money in 1912), and was the Expo’s biggest booster.

Collier chose the central mesa of City Park for the site of the Exposition (editor: there’s more to the story, however – another time). In fact, he made the name change to “Balboa Park”, pushed for California Mission as the style of architecture of the Expo – opposing the more predominant neo-classical style, proposed the Indian background of the Southwest as the main cultural theme, and approved the hiring of known experts in Spanish/Mission Colonial architecture (Bertram Goodhue) and landscaping (the Olmstead brothers).

Apart from all of that, Collier was a founder of the San Diego Museum (now Museum of Man), and supported archaeology research (he was a manager of a New Mexico school of social research and befriended significant local archeologists).

Getting the Exposition rolling was not a cakewalk, as San Diego civil leaders ran straight into efforts by San Francisco to hold a similar event. And more politics were involved. The northern city managed to achieve federal recognition of their exposition – and they did this through the conservative wing of the Republican Party – and defeated San Diego’s attempt for recognition. As Amero described it, “… their triumph caused Collier to join the Progressive wing of the party.”

With the success of the Exposition, after it did finally gain federal support, Collier found his finances hurting, and he had to return to the practice of law and land development. He later left for Chicago, invested in New Mexico, worked in Philadelphia, was an exposition consultant for the government of Brazil, but Collier would always return to San Diego and the practice of law.

Charles and Ella divorced in 1914, and Collier married Clytie who stayed with him to his end. One son – an aviator – was killed during World War I, and the other son became a newspaper man in New York City.

Wonderland Park in Ocean Beach and the Zoo

Originally, Collier’s Ralston Company had built the famous Wonderland Park in Ocean Beach in 1913. But when storms destroyed it three years later, Collier managed the transfer of its animals that had been housed in cages at the northeast end of the park to the newly formed San Diego Zoo in Balboa Park. These were some of the very first animals to be exhibited in what was to become a world-famous zoological site.

Collier Builds Beach Cottages in OB

In 1924, Collier was again selling lots and had an office on Ninth Street. He continued to sell properties in OB, Loma Portal, Wonderland Park, and his firm continued to build beach homes, cottages and apartments from Voltaire Street to Point Loma Avenue.

Once more, he dabbled in local politics, running for County Supervisor in 1932 – unsuccessfully. Two years later, Col. DC Collier passed away, at the age of 63, and was buried at the Masonic plot at Mount Hope Cemetery.

Collier Parks Around San Diego County Today

Today, there are only parks left in his name to remind us of Collier’s civic and community achievements. There are three parks around the County: Ocean Beach, La Mesa, and Ramona.

Ocean Beach – Nearly sold by the City for apartment development in the early 1970’s, OB’s Collier Neighborhood Park is today a small, community park enjoyed by frisbee and horseshoe players, picnickers, dog walkers, and kids of all ages. Unfortunately, the original playground equipment weathered and was removed, and nothing has been built to replace the swings, the slide and other playthings. Although known to OB historians and locals, the park is not well-recognized by community leaders – (one such leader called me over a year ago to ask where it was located).

La Mesa – It is speculation to say that the reason there is a Collier Park in this community is because Collier at one time bought a home and chicken farm in the area. But the park is there, and locals enjoy it, as it has modern playground equipment, plenty of green grass, trees, and a tennis court. There are rumors, however, that the City of La Mesa wants to infill it – which would harm many of its trees.

Ramona – The Collier Park in this east county community has been there for quiet some time; it has tennis courts and picnic areas, and a playground. The Ramona Farmers’ Market has set up shop right next door. Collier had also purchased land out in the Ramona area, and had invested in the Ramona land and water company.

The Case for Col DC Collier as the True Founder of Ocean Beach

Over the course of this series and as we have made the case that Charlie Collier should be considered the “true founder” of Ocean Beach, several points need to be emphasized.

First, in no way is this series or our arguments for our case about Collier meant to diss, put down, show disrespect towards, or throw water on any efforts by Ocean Beach organizations and individuals who are celebrating and promoting the 125th anniversary or birthday of the community.

Our goal is solely to get OBceans to become knowledgeable about our and their history, and to understand the positive and negative aspects of land development. We think it’s great that local civic groups are promoting a birthday for the village; San Diegans and Americans in general are so cut off from our common stories, that any steps towards a more historical understanding of our world, society, city and village is a good thing.

In emails to several OB community leaders, I asked them about how or why they chose the April 1887 date for OB’s birthday. Two were kind enough to respond.

Giovanni Ingolia – President of the OB Planning Board- read the first part and replied:

I found this article very interesting in regards to the history of Ocean Beach. As we all know ones choosing of history doesn’t always agree with reality, for example the myth of Columbus discovering the “New Word” as taught in history classes come to my mind.

When looking at the facts it appears to me the reason Ocean Beach decided to choose Billy Carlson’s date over DePuy’s was because their map covered a much larger area (I believe somewhere around 2200 lots), along with a larger role in the development of Ocean Beach. Also remember Billy Carlson did serve as our Mayor between 1893–1896 meaning sometimes the one(s) in power get to choose our history. Either way both men are of significant importance in the creation of this great community.

Plus I received a very thoughtful response from Denny Knox, Executive Director of the Ocean Beach MainStreet Association. She wrote:

We used the information from Ruth Held’s book that confirmed when the actual name “Ocean Beach” came about. The parcels that Carlson put together were called Ocean Beach in 1887 so that’s the date we used and have used since the 1987 as the 100th birthday of OB.

Lots of people came to this area to spend the day and camped out and a few people built structures etc. before 1887 however that anniversary would be DePuy’s Subdivision Anniversary – I don’t know – it just doesn’t have the same appeal. We’re celebrating and have been celebrating since last April, the 125th Anniversary of Ocean Beach. Since OB folks love this community, it would be hard to celebrate DS (DePuy’s Subdivision).

Also, the downtown district was really established by Carlson and Higgins. As a national Main Street organization, we believe the combination of residential and commercial makes a town or community what it is and gives it a unique personality.

We’re not making a political statement or anything else. We’re just having fun and hoping to raise a little money for replacement, repair and maintenance of projects in the commercial districts. We’re working with the OB Town Council, OB Community Foundation and OBCDC to help them raise money for their causes also.

In Part 2 of the series, we took up the discussion of just who or what is a “founder”. There are suitable definitions, as in someone who “establishes” – to institute permanently, to make firm or stable, to cause to grow and multiply, to bring into existence, to set up, ….

Okay, we have a standard of sorts. But why do we even need a “founder” – why is it necessary to entitle someone with that handle?

And – oh, by the way, didn’t the Native Americans who lived in and around what’s now Ocean Beach – didn’t they actually “found” or establish the place? Indians lived, fished, hunted, and survived on the shores and hills of OB for perhaps thousands of years before the Europeans arrived.

But for some reason, Europeans need to find a “founder” – makes everything and everybody who came later be or feel a part of something. Perhaps, in places where there is so little written history – as here in Southern California – we feel a need for a certain stability given by our placement in this locale and this historic moment.

And even though both contenders for this title come from the more privileged classes of San Diego, and even though we know people make history, we find ourselves discussing the attributes by two from the elite upper class toward the lower classes.

But for whatever reason, as we have founders, we believe the case has been made that Charlie Collier is the true founder of Ocean Beach and not Billy Carlson.

William Carlson did establish the name “Ocean Beach” and he and Higgins drew street names that mostly have been used every since -the partners did built a hotel in OB. And they did sell various lots in their ‘get-rich’ scheme to make as much money as they could grab during their contrived “land rush”.

Yes, Carlson did all these things, but he also lied to people to get them to buy lots in OB. He lied when he told them that “pure” water was available here; he lied when he claimed gold and then oil had been found. And he really packed a whollop with his tale of how his OB railroad – which once completed lasted a whole week – would link up with the much larger Southern California railroad then being built. His train was a complete wreck – built on sand, mud and incompetence.

And yes, Smiling Billy did move on to become mayor of San Diego – our youngest. But in order to get the votes, Carlson again lied – and made absurd claims: there will be steamships to every port, promises of “plenty of work” and “the highest wages”, “electric car lines on every street”; and “transcontinental railroads galore”.

Carlson did work on getting San Diego a railroad – the area’s great challenge of the late 19th century – but utterly failed. Charges of fraud and deceit followed him, as he squandered other people’s money in his quixotic quests to bring the steel of the rail.

In the end, Carlson did nothing of permanence for either San Diego or Ocean Beach – other than giving the village it’s name and the names of some of its streets.

In contrast, Col DC Collier made much more lasting contributions to both the City and OB. Like Carlson, Collier sold lots in Ocean Beach. But he also built the community school, gave away land for parks – parks we still enjoy today, he paved roads, planted trees – and actually lived in Ocean Beach at his beloved Alligator Rock Lodge on the cliffs.

In contrast, Col DC Collier made much more lasting contributions to both the City and OB. Like Carlson, Collier sold lots in Ocean Beach. But he also built the community school, gave away land for parks – parks we still enjoy today, he paved roads, planted trees – and actually lived in Ocean Beach at his beloved Alligator Rock Lodge on the cliffs.

For San Diego – even though he was never elected to office – Collier’s donations and contributions for the tidelands, Balboa Park, and San Diego’s first exposition – all go to demonstrate that this man cut more more of an historical path than Carlson.

Unlike Carlson, Collier also provided utilities and municipal services. And unlike Carlson, Collier’s railroad to OB worked. This achievement more than anything else made Ocean Beach possible. Again, we quote – and agree with OB’s venerable historian – Ruth Varney Held:

“… in 1909, Col. D.C. Collier gave us a good streetcar line that made OB possible. … May 1, 1909, was the day [Collier’s] Point Loma Electric Railway really started OB. …

The trolley was a huge success, and by 1910 Collier had lots of company; there were 100 houses in OB. …

But May 1, 1909, was the day we really remember thanks to “Colonel” Collier, the true father of Ocean Beach.”

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Thank you Kathy! Great compilation of history of OB and its true ‘founder.’ As prior Peninsula Planning Board member, I’ve always thought that those who care enough about a community to push for parks (green is the most ‘relaxing color’ to the human brain), schools, infrastructure and utilities that ‘truly serve the people’ are those who ought to be recognized and remembered for their contributions. I’ve admired the stance of many of OB’s community planning group’s leaders. Way back when the ‘politicians’ changed the name of Collier school (where my spouse’s family all attended) to ‘Correia’, and Collier Park to ‘Cleator Park’ (their ‘contributions’ were so miniscule in comparison) as a REALTOR, I thought that sad. Now all know why OB has more ‘parks,’ a much stronger sense of ‘community’ and why ‘most politicians’ aren’t thought of or even remembered. What a shame that a politician should be able to pilfer from those whose accomplishments earned those ‘recognitions’, from the memory of future generations.